PUBLISHED: MARCH 16, 2013

The story is linked here, but is unfortunately behind McClatchy’s paywall.

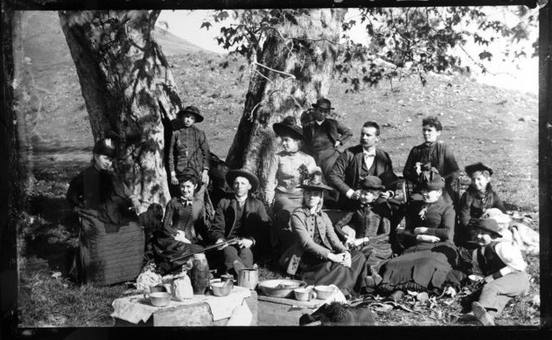

Photo courtesy of the Paso Robles Historical Society. From the collection: Shared Histories: R.J. Arnold’s Photographs of the Central Coast.

The distinct crinkling sound of aged paper filled the hushed basement of the Paso Robles Carnegie Library on a recent morning as several people worked to reveal turn-of-the-20th-century photography from envelopes long forgotten.

“Is it exciting every time you open (one)?” volunteer Helen Luther asked with interest. “Every one is sure a treasure.”

Beside her, with careful hands, volunteer Bruce Van Dyke lifted a glass-plate negative shrouded in dirt and water damage to the light. It revealed an eerie shadow of a man’s portrait captured on the surface.

Van Dyke, seated at a tidy cleaning station, smiled with a hint of excited wonder in his eyes as he continued working.

“You never know. It might be Jesse James,” he said, laughing, hopeful for a glimpse of the infamous outlaw known to have visited his uncle east of Pozo in the late 1800s.

Since August, Paso de Robles Area Historical Society volunteers have been revealing faces from the Central Coast’s affluent and minority families in a collection of 2,000 glass-plate negatives. They are the work of late photographer Richard “R.J.” Arnold.

Experts say the negatives — the largest collection of historical items the Paso Robles society has ever received — help weave an intricate tale of the county’s wealthy and cultured past through the faces of those who inhabited the area so long ago.

While the negatives are not dated, business registries in San Luis Obispo show that Arnold had a photography studio on Monterey Street from at least 1888 to 1893.

The historical society has since put some glass plates and prints enlarged by Pasadena curator Anthony Lepore on exhibit in a collection titled “Shared Histories: R.J. Arnold’s Photographs of the Central Coast.”

“It really shows the social tapestry of the time,” historical society Vice President Karen MacLaurin said. “What you see here is amazing because he (Arnold) was very egalitarian. A lot of photographs of people are of different ethnicities, which at the time was very unusual.”

While local history groups have received hundreds of glass-plate negatives over the years, Arnold’s artistic style in capturing his subjects — white, black, Chinese, Hispanic and others — sheds more light on how things once were.

An assortment of families, soldiers, Masons and children are displayed on the fragile glass.

His subjects are posed with elaborate backdrops and period clothing. Sometimes they are together; showing a pair of siblings, a widow with a hunting dog or a mother trying to make her ringlet-haired baby laugh.

Photo: David Middlecamp

Props were also used: Aman poses in a three-piece-suit with a violin. A Masonic-looking fellow is shown complete with his sash-and-sword regalia. Those details bolster the importance of the find, local officials say.

“That’s what makes that collection so significant,” said Erin Wighton, chief administrative officer of the History Center of San Luis Obispo County.

Without added details that help place who these people were and how they lived, “then it’s just that, a glass plate.”

She doesn’t value the negatives in terms of dollar worth.

“Value is really based upon what we know about the image and the input it brings

into the historical narrative of the area more than an actual dollar amount,” she said.

As a bonus to today’s researchers, Arnold also marked his negatives and envelopes with his customers’ names.

Among them, as shown in the exhibit, is a young boy from the Dana family. While researchers have not yet verified who the boy is, Dana is the name of the family linked to the historic Dana Adobe in Nipomo. An earlier publication of Arnold’s plates in the 1990s also includes the names Quintana and Higuera — notable street names today in Morro Bay and San Luis Obispo.

Photographer as artist

Glass-plate negatives cleaned so far — using a dash of Ivory soap, water and a cotton ball — show men in dapper suits, young boys in ruffled dresses common for the era and women dressed in refined, layered ensembles.

Negatives from his work appear to depict the wealthy, although Arnold may have dressed his customers in costumes he kept in the studio, researchers say.

His work also takes viewers out into the county’s landscape — which those close to the works say is part of what made Arnold’s style so artistic and unique for a portrait photographer in that era. Most photographers of the day limited their work to the studio or focused on structures.

“What really stood out to me is the artist in him,” said Dan Krieger, retired Cal Poly history professor. “Photographs in the landscape were often architectural, so focusing on the people of the time outside of the studio was really something.”

Arnold also photographed a butcher shop with workers standing before a backdrop of hog and cattle carcasses strung high above, and captured the idyllic countryside around Hollister Peak before Highway 1 was a state highway.

One of the most detailed photos shows an image of what historians say are churchgoers having an outdoor picnic under the shade of a sycamore tree. Eight women, three men, two boys and a dog are seated in the grass after apparently enjoying a meal among a vast layout of wooden crates acting as small tables for tin cups and bowls. Details pop from the picture, which was later enlarged for the exhibit, including utensils, a large glass jar with its shiny lid sealing in a pickled dish and a can clearly displaying the lettering for condensed milk.

All but one picnicker wear hats, and all are finely dressed. Volunteers pointed out one man’s double-barrel shotgun and snickered about how he may have been looking for a squirrel.

History

Photo: David Middlecamp

Photographers in the 1800s followed the money, according to Krieger, because affluent families were the only ones who could afford the 50 cents to $1 that photographers charged then.

Some published information on Arnold suggests he may have also been following California’s historic missions.

Krieger and his wife, Liz, started interviewing older residents in the 1970s to get their stories written down. He remembers some of them telling stories about when their parents and grandparents went into Arnold’s shop to get their portraits done.

Arnold’s photos highlight San Luis Obispo during a key time in the area’s history, Krieger said.

“It shows who we were really — the diversity is the first indicator, and the very fact the photographer was here meant prosperity,” Krieger added.

The ethnic diversity of those pictured also “suggests we’re becoming a very multicultural society in the 1870s,” he noted.

Arnold arrived when the county was unlike it is today. It was before the coming of the Southern Pacific Railroad and, even, Cal Poly, which opened in 1901.

It was an age led by the Steele Brothers from Marin and San Mateo counties who set the framework for the local area’s dairy boom.

Families and immigrants flocked here to make milk and cheese, Krieger said, and many people became quite wealthy with their ranching operations, with lasting effects into the present day.

The original settlers and immigrants were of various cultures, he said, including the Portuguese from the Azores Islands, the Italian Swiss “and, of course, the Chinese were already here.” Some of these cultures appear in Arnold’s sophistic portraits, including a Chinese man holding a book and a fan.

The photographer Richard Arnold was born June 28, 1856, in England, historians say, and died May 19, 1929.

In his teens, he moved to America, where he eventually set up portrait studios along California’s Central Coast.

Allan Ochs, a researcher with the San Luis Obispo County History Center, says it appears he was in his 20s and 30s when he worked in San Luis Obispo. The county’s registrar of voters described him as having blue eyes and light hair.

Historians believe he traveled to San Luis Obispo from Santa Barbara, and then later ventured to Alameda, eventually settling in Monterey before he died.

In his obituary published in the May 20, 1929, edition of the Peninsula Daily Herald, a Monterey newspaper at the time, Arnold was described as a “pioneer local photographer” who died after “a month’s illness” at age 73. The obituary goes on to say Arnold came to Monterey in the late 1890s and was one of the area’s first photographers.

The obituary also gives accolades to his rare photos.

“Arnold’s collection of pictures of the California Missions in their original state is irreplaceable, the only one in existence and valued highly,” reporter W.F. Gleeson Jr. wrote. The article

also said “subjects of beauty or historical interest were his chief delight.”

In San Luis Obispo, Arnold set up in what is the downtown today. It’s not clear whether Arnold moved around, Ochs said, but at least one of his shops was near the Sinsheimer general store on Monterey Street.

A photograph of his downtown shop, complete with period signage and architecture, is included in the Paso Robles exhibit.

Arnold’s work with glass-plate photography, invented in 1851, utilized an advance in technology at the time. The process involved producing a negative on an 8-by-10-inch glass sheet that could be cut in halves and quarters to make a number of prints in many sizes. Photographers would paint one side of the glass with a home brew chemical emulsion and place it into a camera. Each sheet would, typically, make one exposure.

One of Arnold’s glass negatives showed two exposures side by side on a 4-by-5-inch single plate, which impressed the volunteers cleaning them. The process became obsolete with the advent of film in the late 1800s.

Donor Randal Young

The story of where Arnold’s negatives were after they left his portrait studio in downtown San Luis Obispo and arrived at the Paso Robles historical society more than a century later is mostly a mystery.

Jacqueline D. Marie, a local personal property appraiser, donated the collection of plates on behalf of Randal Young’s San Miguel estate.

She and Young were lifelong friends, she said.

“Randal gave me the glass plates and then I donated them to the society in his memory,” Marie said.

Young was born and raised in Atascadero, she added, and he loved the area’s history. Enter lifetime San Miguel resident Sharon Rose. She remembers working at the San Miguel Post Office when Young, sometime in the 1990s, stopped in to tell her about how he had recently bought a box of glass-plate negatives in the Atascadero area.

“He told me that he picked them up at a sale and he was excited at the find,” Rose said. “I don’t know if it was a yard sale or community sale, but he looked in the box and there they were.”

She wasn’t sure how much he paid for them.

In 1995, Young contributed images of some of the glass plates for a book titled “Glimpses of Childhood in the Old West. 1840-1940.” While the time span listed in the book is much longer than when Arnold was said to be in San Luis Obispo, the glass negatives showed similar artistic styles, including portraits of children in elaborate period attire, each with charming details down to jacket buttons and shoes.

Some of the plates included in that book are also included in the Paso Robles society’s donated collection.

After 1995, it seems that Young stashed the negatives in an 1873 brick building that he owned in San Miguel, until he later gave them to Marie.

The historical society also heard that the plates were stored in a barn at some point, which exposed some to the elements, although Marie said she only knows of the building.

Marie said she wanted to honor her friend by donating the boxed collection to the Paso Robles historical society on the promise that they wouldn’t leave the county.“The descendants of many of these children continue to live in the vicinity,” Marie said. “It’s those descendants that I felt needed access to this and know the photos are out there.”

Photographer David Middlecamp contributed to this story. Check out his Photos From the Vault blog at http://sloblogs.thetribunenews.com.